10 May 1869: Transcontinental railroad completed as the ceremonial final spike is driven at Promontory Point, Utah

Iron Rails, Iron Men, and the Race to Link the Nation: The Story of the Transcontinental Railroad

by Martin W. Sandler

Nonfiction/History

Recommended for: Dialectic students

224 pages

Publisher: Candlewick (2015)

On this day in 1869, the Union Pacific railroad and the Central Pacific Railroad were connected in the middle of the Utah desert, at Promontory Point. The Central Pacific Railroad began building in Sacramento, California and had the tough job of forging a path east through the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Of the two companies, they laid down fewer miles of track, but had the more difficult job. Chinese laborers were plentiful in California and were very hard workers; more than 14,000 were working in the terrible, dangerous conditions pervasive in the Sierra Nevadas during the height of construction, and many would lose their lives. The Union Pacific Railroad began around modern day Omaha, Nebraska and built westward across the plains. The majority of the workers for the Union Pacific were Irish-American immigrants and Civil War veterans. Government incentives in the form of land and $48,000 per mile of track encouraged the companies to be very competitive with each other and resulted in shoddy, cost-cutting practices.

Railroads powered by steam locomotive had been around since 1830, linking many east coast cities, and, by 1850, the railroad stretched past the Missouri River. For those heading for California and other far west locales, however, travel options were lengthy and expensive. By sea, around South America's Cape Horn, one could expect a journey of roughly six months and expenditures equaling $20,000 in today's funds. Slightly shorter in duration and expense was the option of taking two ships with a hazardous and disease ridden portage across the Isthmus of Panama in between. For most, the only option that was remotely affordable was joining a wagon train and crossing the plains and the Rocky Mountains.

Having a railroad that went coast to coast had so many ramifications that the day the two companies' efforts joined together is considered one of the most important in American history. The driving of the (literally) golden final spike was a tad bit anti-climactic, though. Each railroad's owner missed the spike on their ceremonial swing. Leland Stanford from the Central Pacific Railroad at least hit the tie, but his fellow owner, Thomas Durant of the Union Pacific, hungover from the previous night's celebration, did not even come close. At 12:47 p.m. the ceremonial spike was successfully driven home by a railroad worker whose name is lost to history.

It is easy to see and understand the many pluses that the transcontinental railroad brought. Travel was certainly easier and cheaper--that $20,000 (today's funds) price tag dropped to a far more reasonable if still pricey $3,000, and the journey could be accomplished in less than a week. Settlement of the West increased exponentially. The U.S. economy became a two-way street with western raw materials flowing east and eastern finished products flowing west. International trade also increased, as Asian products went east along the railroad; a shipment of Japanese tea was among the goods on the very first eastbound freight train. A man by the now household name of Aaron Montgomery Ward realized the railway's potential to ship products all over the country without needing a single storefront and founded the mail-order catalog Montgomery Ward just three years after the driving of the final spike. It now became realistic to purchase large items like pianos and have them delivered out west. In later years, the catalog would even sell pre-fabricated homes (think Ikea flat pack, gone gargantuan).

In all the giddy pride that the railroad brought, its downsides were often overlooked. During its building, western forests were leveled as thousands upon thousands of trees were felled to build the railroad, bridges, tunnel supports, and towns along the way. The influx of population that followed further devastated the pristine western wilderness that was suddenly no longer either so wild nor so pristine. Racial conflicts also increased as men traveled west looking for jobs and were forced to compete with the large number of hard-working Chinese who would work for lower wages. Big game hunters from the East could suddenly go west on hunting trips, and they did--by the thousands--driving game numbers down to numbers that they often could not recover from. This was especially true of the buffalo, who also suffered from disruptions in their migratory patterns due to tracks and towns that sprang up. Their slaughter was especially disastrous for the Native Americans who had judiciously hunted the buffalo and relied on them for their survival.

Few would argue that it was by the continent's original inhabitants that the greatest effects were felt. As the railroad brought in ever larger numbers of settlers who forged farms, ranches, and towns on Native American hunting grounds, the Natives were put in an untenable position and fought back. The violence against American settlers brought the might of the U.S. military down upon the Native Americans. These territorial battles--combined with the loss of game and natural resources and increased spread of European diseases--tolled the death-knell for many tribes.

While marveling at the march of human progress and the good it brings, it is also important to remind our children of the costs. As they go through their study of history, it is a fact they will be confronted with often. The question of whether the less driven Native Americans were doomed from the very first European foot to tread on the shore of North America is a heavy one and one debated at the highest levels of academia. Many argue that in the acquisitive rush more peaceable people get trod underfoot. Others argue that social Darwinism is a fact, sad though it may be. Subjects such as the joining of the rails that day in Utah provide a wonderful window for debate and helping students to see that every issue is multi-faceted and there is more than one narrative in every story.

The Transcontinental Railroad

by John Perritano

Nonfiction/History

Recommended for: Grammar students

48 pages

Publisher: Children's Press (2010)

Series: A True Book: Westward Expansion

Nothing Like It In the World: The Men Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad 1863-1869

by Stephen E. Ambrose

Nonfiction/History

Recommended for: Rhetoric students/adults

432 pages

Publisher: Simon and Schuster (2001)

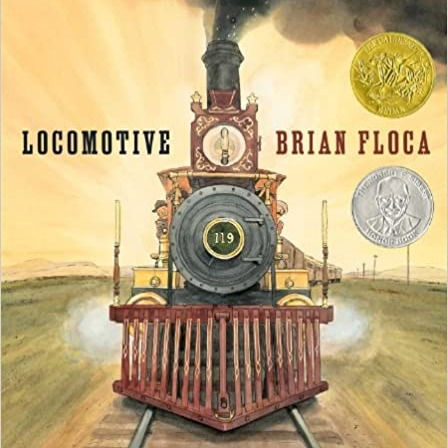

Locomotive

by Brian Floca

Nonfiction/Picture book

Recommended for: Grammar students

64 pages

Publisher: Atheneum/Richard Jackson Books (2013)

Comments